PHILIPPE BOLTON

flageolets & recorders

A short history of the French Flageolet

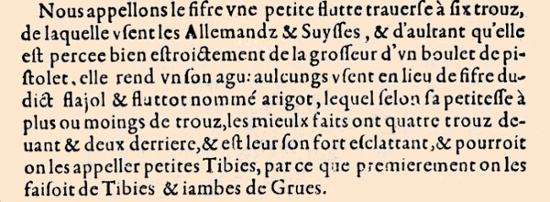

The flageolet probably dates back from the end of the XVIth century. It is said to have been invented by Sieur Juvigny de Paris who played it in 1581 in

Le Ballet Comique de la Royne, the first courtly ballet to be performed and printed in France.

However the text suggests that the instrument would have been panpipes rather than a flageolet.

Thoineau Arbeau (1588)

Thoineau Arbeau mentions the instrument in his Orchésographie as a possible substitute for the fife in military music. He uses the terms flajol and

arigot (which was probably an earlier name for the instrument) and describes the position of the six holes, four in front and two behind.

|

|

Marin Mersenne (1627)

There is an article on the flageolet in Marin Mersenne's Harmonie Universelle published in 1636. The author describes the position of the tone holes, four in front and two behind. He also says that there are two possible positions for the hands, either using the thumb and the first two fingers of each hand, or the thumb and first three fingers of the left hand and only the thumb and index finger of the right hand. This second method became obsolete later.

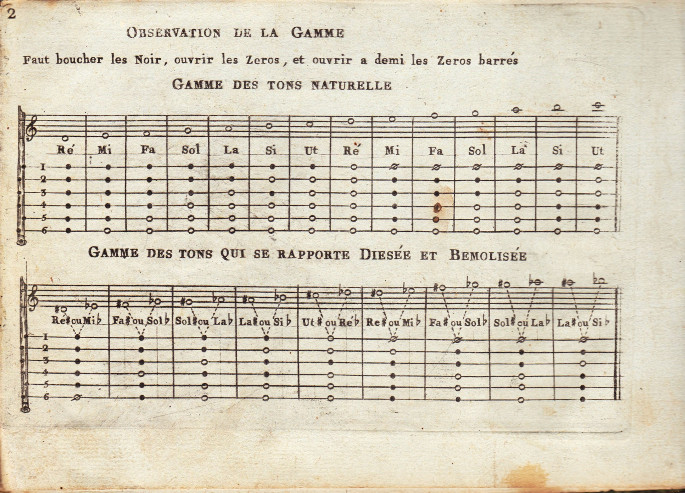

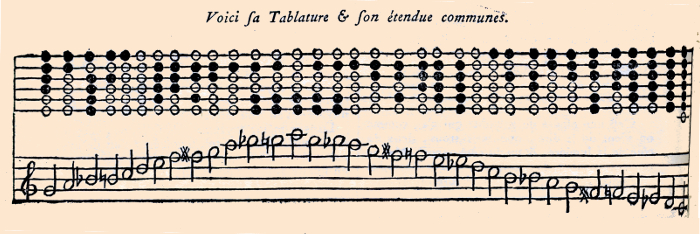

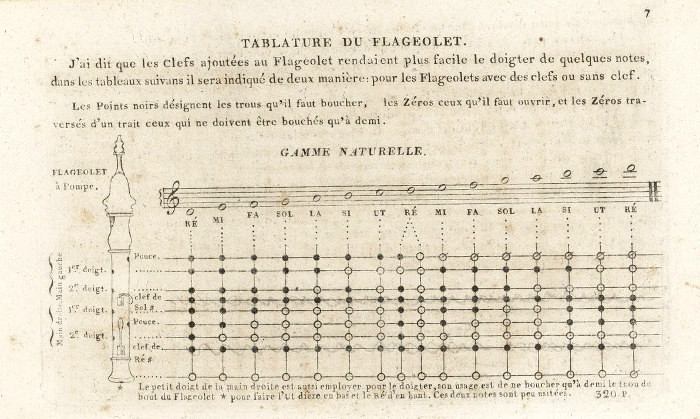

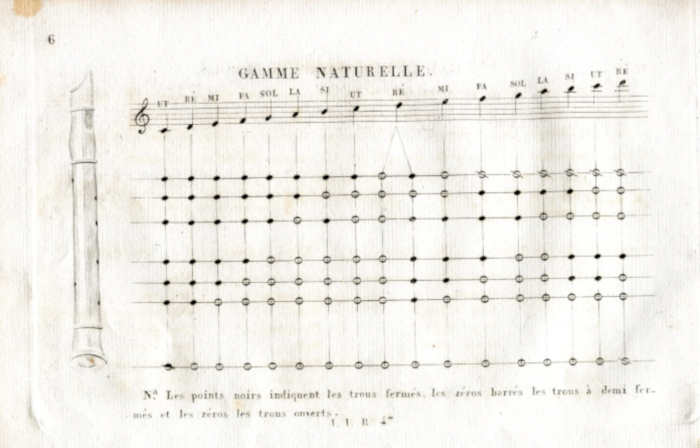

In his text Mersenne says that the range of the instrument is a fifteenth (two octaves). Each horizontal line in the chart below represents one of the holes. The black marks indicate those that must be closed for each note. He also suggests partially closing the bell to play one extra note lower down when all the holes are closed.

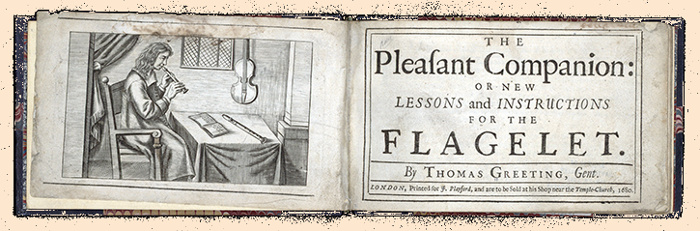

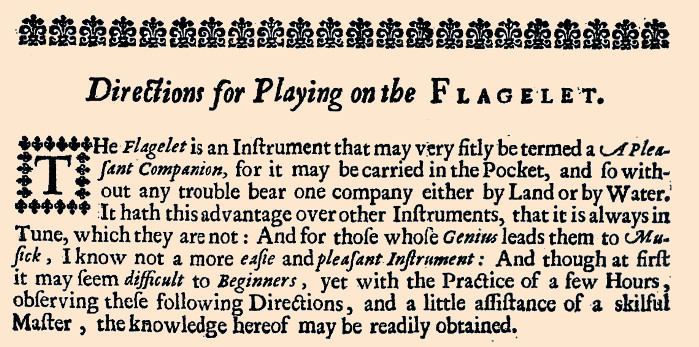

An early method, The Pleasant Companion (1675)

The flageolet was not a specifically French instrument in the 17th century. The earliest known method for the intrument, Thomas Greeting's Pleasant Companion was printed in England in 1675.

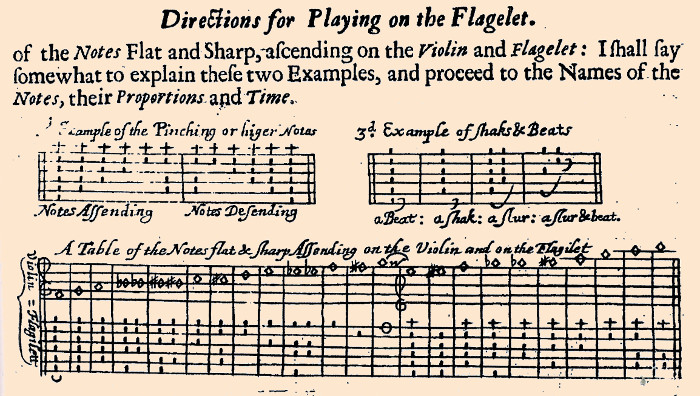

Greeting's description of the flageolet

His method was probably intended mainly for amateur musicians since the he uses tablature or dot notation instead of conventional musical notes.

A fingering chart

Pieces in dot notation

Among Greeting's pupils there was a friend of his, Samuel Pepys, who mentions the flageolet several times in his diary.

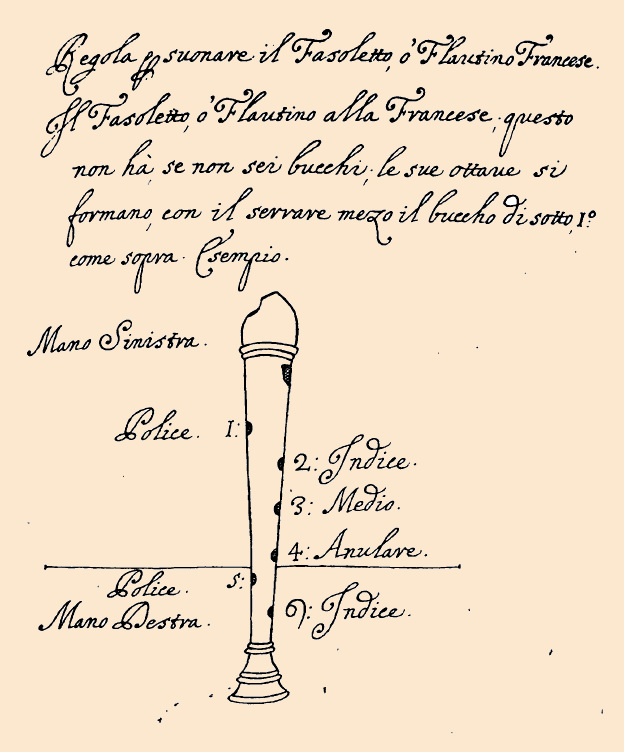

Bismantova (1677)

The French flageolet was also played in Italy at the end of the seventeenth century as can be seen in Bartolomeo Bismantova's Compendio Musicale. In this drawing he shows us one ot the two ways of fingering the instrument.

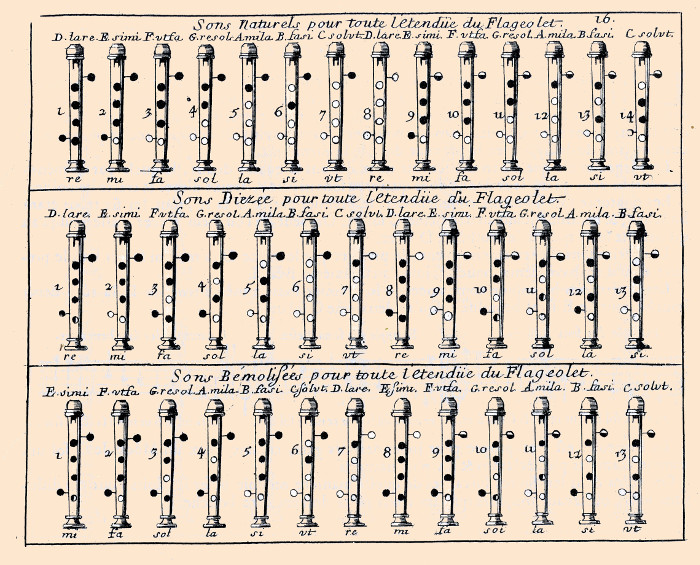

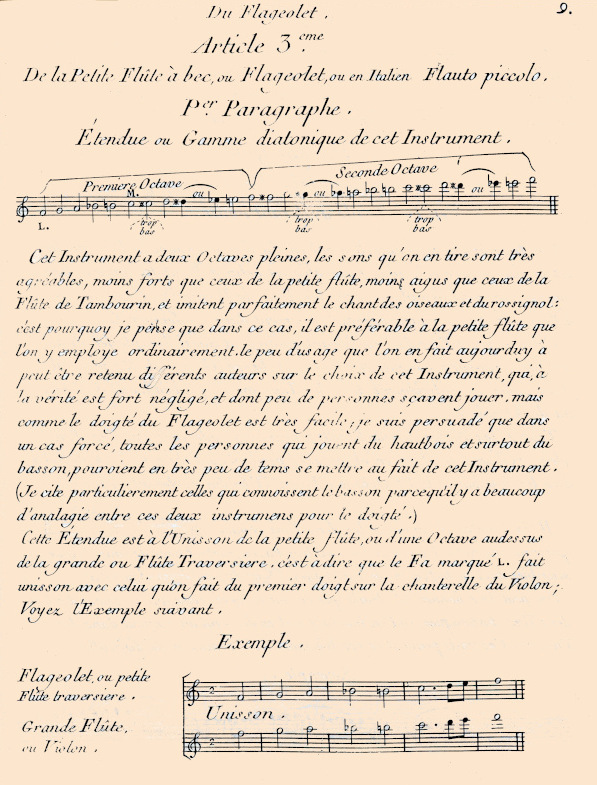

A French method by Jean-Pierre Freilhon Poncein (1700)

Freilhon Poncein wrote a chapter on the flageolet in his treatise La Véritable manière d'apprendre à jouer en perfection du hautbois, de la flûte et du flageolet. (The Real way of perfectly playing the oboe, the recorder and the flageolet). He indicates that the instrument can play fourteen natural notes, and that it is possible to force the instrument to play one step higher, giving a range of two octaves. He recommends closing the first four holes with the left hand, and the last two with the right hand, as in Mersenne's second method.

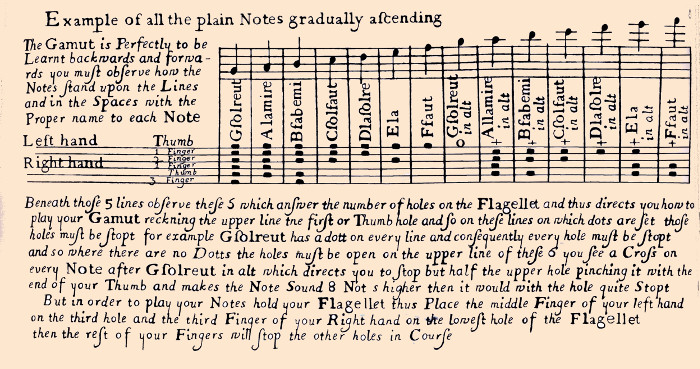

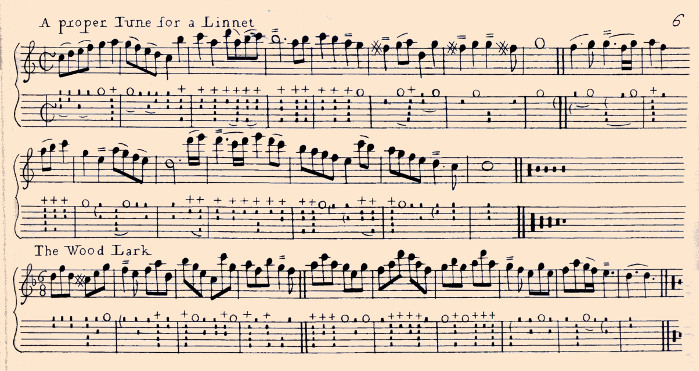

Another English method, The Bird Fancyer's Delight (ca 1730)

The flageolet could be used for teaching tunes to cage birds to increase their value. This method contains a variety of suitable airs for different species.

Both musical notes and Dot notation are used together here.

Diderot & d'Alembert's Encylopédie (1751 - 1772)

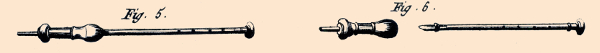

The instrument is described in Diderot & d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, in two forms, the large flageolet (fig.7), and the bird flageolet (fig. 5 & 6), which was smaller and was fitted with a windcap called la pompe. The shriller bird flageolet was sometimes used for teaching tunes to canaries and other birds.

Diderot also mentions that the large flageolet only differs from the other in that it has a beak instead of the windcap, and that it is made in one piece

The author specifies that the flageolet has a range of a fifteenth (two octaves), as do Mersenne and Freilhon Poncein.

Francoeur

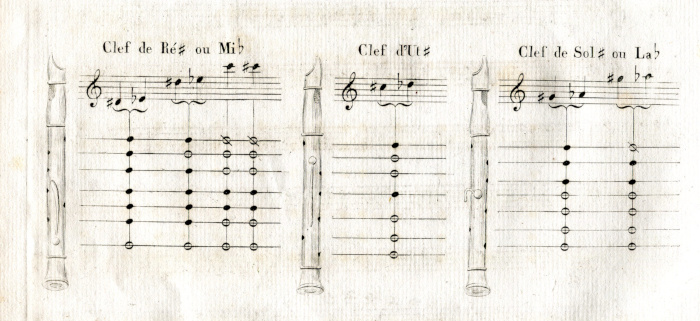

There is a chapter on the flageolet in Louis-Joseph Francoeur's le Diapsson Général de Tous les Instruments à Vent (1772). The example given is for a flageolet in F, which is not a very common size.

Bergeron

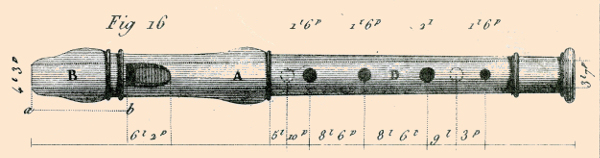

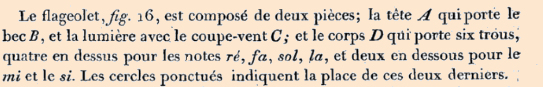

The picture above, from P. Hamelin Bergeron's Manuel du Tourneur (1792) shows a flageolet à bec of this period, in two parts with a recorder type mouthpiece. The instrument's popularity could explain its presence this of manual of wood turning.

The 19th century

The windcap mentioned in Diderot's Encyclopedia, came into general use during the 19th century.

The drawing of a flageolet with a windcap from Victor Charles Mahillon's Eléments d'Acoustique" (1874)

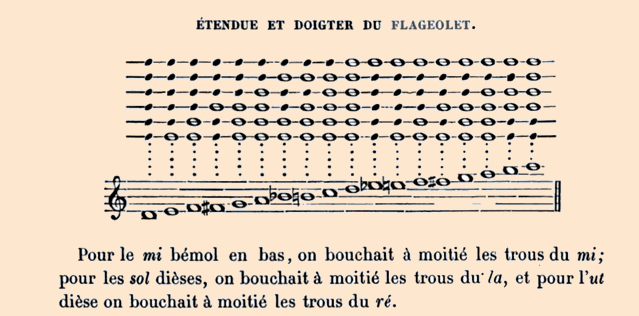

Until then French flageolets were made in different keys, particularly in D, F, G and A. From 1800 onwards the instrument in A became the rule. However, for ease of reading fingering charts and pieces were often written as for a transposing instrument in D, as shown in this chart from Fétis' Histoire Générale de la Musique (1872) for a keyless flageolet.

The author also explains how to play semitones on the flageolet by partially closing certain holes: For playing low E♭ the hole for e would be half closed, for G# the hole for a would be half closed and for C# the hole for D would be half closed.

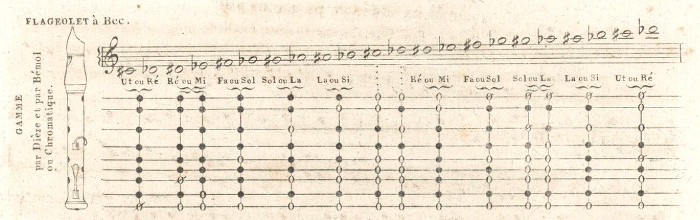

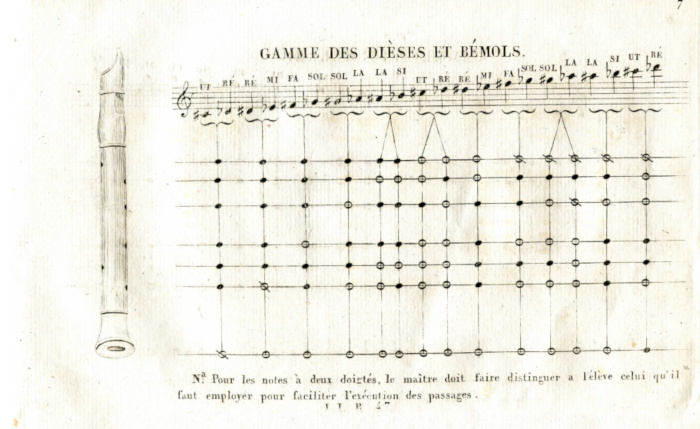

Here is another chart showing the same method for playing D# (ø = a partially closed hole) and a fork fingering for G#.

In order to overcome these difficulties the flageolet was little by little fitted with keys so as no longer to require the use of leaking holes or fork fingerings,

of which the most common were for D# and G#.

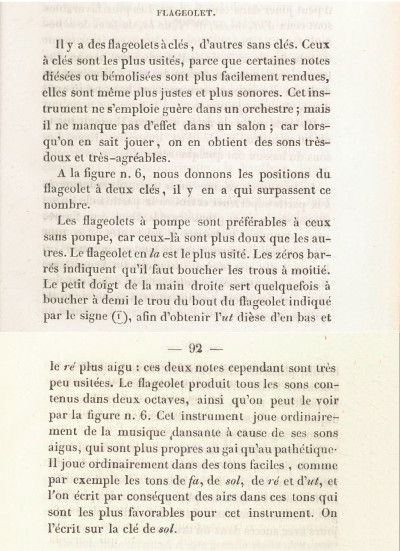

In his book, Les Secrets de la Musique, published in 1846 Pierre Rigaud gives this description of the instrument, laying emphasis on the advantages of the keys, and the beneficial effect of the windcap on the tone quality.

(Source : BnF)

Here is a translation of some highlights of the text:

"Flageolets with keys are the most commonly used because some sharps and flats are easier to play, better intonated and louder...

Flageolets with a windcap are preferable to those without because their tone is sweeter...

The flageolet in A is the most commonly used...

The little finger of the right hand is sometimes used for

partially closing the bell in order to play low C# and high D...

The flageolet can play all the notes over two octaves...

The most favourable keys are F, G C and D... Its music is written in the treble clef."

The named keys and notes (low C# and high D, for example) suggest its use as a transposing instrument in D.

The following chart, from Eugène Roy's method for the flageolet, is again intended for a transposing instrument in D and makes use of these two keys. The bottom hole on the chart is the bell, which can be partially closed with the right hand little finger as indicated in the text above.

(Source: BNF))

In his undated NOUVELLE MÉTHODE DE FLAGEOLET Viguier-Saunier shows both techniques (partially closed holes and the use of certain keys) in separate charts.

Different key arrangements can be seen here.

This was the flageolet's golden era. It was played in balls and other festivities and excellent musicians like Bousquet, Collinet and others wrote and played virtuoso pieces for it. The instrument was also popular in England.

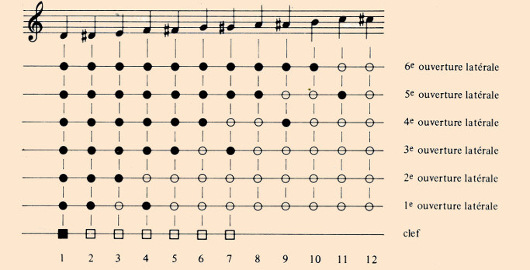

Here is a translation of a text by Victor Charles Mahillon, in which he describes the flageolet in 1874, and gives a chart for the notes of the first register. Strangely Mahillon does not mention the use of the thumb hole as a register hole for playing high notes, as was customery on this intrument, and can be seen on the other fingering charts above. There may also be a mistake regarding the key, which should only be open for C#.

"The flageolet is a transposing instrument. This name is given to all instruments whose intonation does not correspond to the written note or one of its octaves, high or low.

With six tone holes and one key the flageolets emits the following fundamental notes

The instrument being of small size it is almost impossible to place all the holes on the same line without hindering the movement of the fingers, which is the reason for boring four holes on the front and two

behind. The fundamental notes in this chart leap up an octave with higher breath pressure. The scale is completed at the top with a few notes making use of the third harmonic

On very old instruments low d# was inexistant. On modern ones keys have been added to replace the fork fingering necessary for playing notes 4, 7, 9 and 11.

The flageolet's fingerings are largely the same as those of the instruments with small holes still used nowadays, which is why we will examine a few details.

Holes n° 2, 4, 5, and 6 have a double function. They give repectively f#, a, b and c#, and by closing the preceding hole f, g#, a# and c. This is the technique of fork fingerings."

The French flageolet seems to have fallen into disuse in the beginning of the twentieth century, at the time of the Great War.